Tarifa Salem: Aesthetics and authenticity

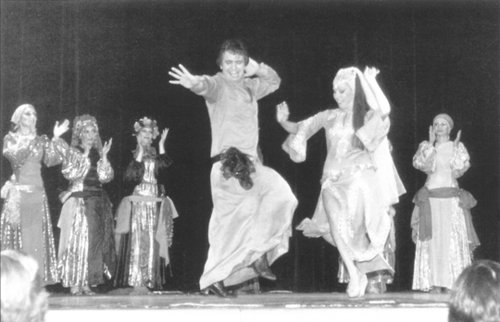

Tarifa Salem is a Middle-Eastern dance artist and instructor. Her early exposure to the music and dance of her Lebanese heritage set the stage for her dance career. Her uncle and mentor, the late great Ibrahim Farrah, helped her develop and refine her art and inspired her to pursue graduate studies in dance in the late 70s. She performed with the highly respected NYU-based modern dance company, Kaleidoscope, and performed with the Ibrahim Farrah Near East Dance Group from 1979-1982, and was a regular featured dancer at popular Middle Eastern nightclubs in NYC, NJ and PA. She currently teaches Middle Eastern Dance in Jacksonville, FL, and is a personal trainer and fitness instructor. She has been a featured presenter and featured performing artist for workshops, clinics, and master classes throughout the eastern US.

Riskallay Riyad hosts Tarifa Dec. 2nd and 4th for Oriental and folkloric workshops, as well as a presentation on “The Farrah Factor”.

Younger dancers are not as familiar with Bobby Farrah’s work and talents. What are the most important things you would like them to know about him?

I would like them to know how unbelievably committed Bobby was to his art, how much of himself he gave to maintaining traditional (dance) forms without sacrificing artistry and theatrical aesthetics, and how devoted he was to maintaining a standard. He was an extreme perfectionist and had an amazing vision for how to present his dances on stage.

Bobby grew up in a very traditional Lebanese family. Quoting him in his article “The Lebanese Chapters” from Arabesque Magazine, “My childhood in Pennsylvania, as I realize from the perspective of time, would not have been much different had I been born in Lebanon.” He embodied the essence of the dance of his heritage by being immersed in the culture, but his intellectual capacity and thirst for knowledge led him in the direction of research. A Duke Grant took him to Lebanon in the early 70s, where he filmed a family of Bedouin gypsies performing authentic dance rarely seen outside the east, (and shown in his “Rare Glimpses” DVD). He was editor of Arabesque Magazine where he created a space to discuss “ethnic dance”. This became a forum where he engaged other researchers and anthropologists to share their studies on dances of indigenous folk, as well as modern nuances of ethnic dance. Bobby won the prestigious Ruth St. Denis Award presented by La Meri in 1979 for his choreographic expertise in bringing to the stage the best of the myriad of Near Eastern dances, and for being an untiring pioneering in his chosen field of ethnic dance.

I would also like people to know what a kind person he was, and how truly loyal he was to family, friends, students, and respected colleagues. Not only was he dedicated to sharing knowledge about his art, he shared his joy in expressing it. On a personal note, I will always cherish the laughter he brought into my life and that of my family. He was the best uncle, brother, son, godfather, and friend that anyone could ever ask for.

Why is the study of folkloric dance an important part of an Oriental dancer’s education?

Studying the movements of cultural dances seen at celebrations, community gatherings, and festivals specific to a time and place help the student to understand characteristic gestures and facial expressions, as well as the overall essence of a particular style. Nuances such as carriage, use of space, and dynamic among various populations of a people (men, women, married, single, and so on) should be addressed in folkloric classes so that students will develop an understanding of traditions and mores within a culture. The “how and why” of a dance gives historical and cultural perspective. For example, there are circumstances that define the appropriate style of dance to be performed within a given time or a particular space, and of course, age and gender.

Oriental dance today is very different than 20 or 30 years ago. How do you see the Oriental dance study and performance evolving?

I don’t see what I refer to as Oriental Dance as having changed that much. I began my professional career in 1978 and have been fortunate to enjoy performances by artists who have maintained the tradition that I am familiar with 40 years later. I have seen styles that depart from those traditions, but many young dancers I have seen have obviously inherited all the elements I consider to be essential in the Oriental genre from their instructors who have dedicated themselves to maintaining the essence of the Eastern Dance.

All dance evolves, but the elements remain the same in traditional Oriental dance. Traditional costume, music, and technique remain, but an artist may take liberties with form and be considered authentic according to La Meri’s definition in her book Total Education in Ethnic Dance. We take liberties in traditional Oriental dance when we choreograph for the stage and set a time limit, but it is still considered Oriental. If a style has taken liberties with costume, music, and form, but the technique remains the same, it becomes a “Neoclassic” form or what we call a “creative departure”. Unfortunately, some artists lose sight of the cultural base and it loses its Oriental essence; therefore it can no longer be defined as Oriental. It is still art and if an artist’s base is strong it will truly inspire. You must have a strong traditional base to depart from, however, if you hope to maintain the essence of Oriental dance. To quote La Meri, “One must understand not only the authentic forms but the motivations, else one loses the essence of ethnicity, and the result is a mishmash of schools with no aesthetic value.” (Total Education in Ethnic Dance)

- November 22, 2016

- 3963

- Belly Dance

- Comments Off on Tarifa Salem: Aesthetics and authenticity